Sigmund Freud lies awake late one night, sweaty, thinking about the Sand-Man.

He throws handfuls of sand in their eyes, so that they jump out of their heads all bloody;

His little ones sit there in the nest and have hooked beaks like owls, and they pick naughty little boys’ and girls’ eyes out with them. [1]

hooked beaks, bloody eyes

Freud turns over sighing heavily. This is not acceptable, this fear, this “uncanny” feeling. It must be controlled. He rolls out of bed and staggers to his desk, lights a candle. Head in hands, he steadies his worried breathing. He jots down a two and a half page summary of Hoffmann’s masterful short story “The Sand-Man.” His hand wobbles slightly when he comes to Spin round, fire-wheel! but does not stop moving swiftly across the page. Finally he places his pen down calmly and analyzes his summary. There. There lies his fear, leaking darkly into the paper’s fibers. His irrepressible feelings of disgust and horror. His uncontrollable astonishment.

The Sublime and the Uncanny

Freud misuses the term “sublime” when he states that it is the opposite of the uncanny: “[aesthetics] in general prefer to concern themselves with what is beautiful, attractive and sublime—that is, with feelings of a positive nature…rather than with the opposite feelings of

repulsion and distress.” [2] In fact, Edmund Burke solidified the definition of sublime regarding aesthetics in his treatise “On the Sublime and Beautiful” in 1757 as “Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime;” [3] The sublime, then, is deeply connected to fear and horror, not to feelings of a “positive nature.” Burke further adds “It [the sublime] is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.” The uncanny and the sublime both produce an overpowering emotion, frustrating any reasonable thought process. Freud lies awake late one night, sweating.

Astonishment

The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature, when those causes operate most powerfully, is astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other, nor by consequence reason on that object which employs it.[4]

We are near the

Freud turns over, sighing heavily.

Aha! aha! aha! Fire-wheel—fire-wheel!

Spin round, fire-wheel! merrily, merrily! Aha! wooden doll! spin round, pretty wooden doll![7]

Nathanael is driven mad by his sense of the uncanny. He becomes astonished, witless. When he sees

Categories and Reason

After some thought and a cup of coffee, Freud figures something out.

Freud cannot leave the eyes alone. Birds pick at them in his dreams, and he rubs them in his sleep. His wife has long since left his bed for a more silent chamber. His mutterings fill the house. The eyes, the eyes. What is it about the eyes?

There is rifling through old papers, heavy books. The smells of tobacco and ash fill the house. Here! The fear of damaging or losing one’s eyes is a terrible one in children. Bloody. Handfuls of sand. Many adults retain their apprehensiveness in this respect, and no physical injury is so much dreaded by them as an injury to the eye.[11] Fear of losing our eyes, and dolls coming to life. I feel I am grasping at the answer to these “uncanny” feelings. Categories and reason. But…why still can’t I sleep?

The Undead

Many people experience the feeling [the uncanny] in the highest degree in relation to death and dead bodies, to the return of the dead, and to spirits and ghosts.[12]

We watch, crouching together on the edge of a massive windowsill, as Jonathan Harker pries open a coffin in the Count’s chambers. Inside lies the form of a man, eyes wide but empty, sleeping without breathing. We share Jonathan’s disgust at this undead thing, and cheer when he raises a shovel over the Count’s face to smash it in. But something uncanny happens. As Jonathan strikes, the Count’s head turns and stares at him, those eyes with “all their blaze of basilisk horror.” The shovel glances of the Count’s forehead and forces closed the lid of the coffin. And Jonathan: “The last glimpse I had was of the bloated face, blood-stained and fixed with a grin of malice which would have held its own in the nethermost hell. I thought and thought what should be my next move, but my brain seemed on fire, and I waited with a despairing feeling growing over me.”[13] All motions are suspended.

Learning to Die

The premeditation of death is the premeditation of liberty; he who has learned to die, has unlearned to serve…To know how to die, delivers us from all subjection and constraint.[14]

Montaigne is right; overcoming the fear of death would lift a great burden from most of us, who store death at the edges of our brains like a rusty silver ring. When a friend or relative dies, we take it out and polish it briefly, but we rarely ever look closely enough to see our own reflections gleaming dangerously within the shine. But even if we did become comfortable with our own deaths… even then…what about the dead coming back to life?

In Tim Burton’s “Batman Returns,” Selina Kyle falls from a high window and dies, sprawled out in crooked angles, on the wet concrete below. Cats appear from all dark corners of the city and begin, as it first appeared to me at that young age, to eat her. When my mother informed me that the cats were not eating her, but in fact licking her back to life,[15] I was even more terrified. Was she not then one of the undead?

Or again: Beloved, a ghost, pregnant and smiling, in the doorway.[16] The dead reproducing, coming to life. Uncontrollable astonishment.

Psychological Truth

Clara. Clara is the smart one. She is Hoffmann’s scientist. Yes, for she writes to her steadily slipping lover Nathanael, “I will frankly confess, it seems to me that all the horrors of which you speak, existed only in your own self, and that the real true outer world had but little to do with it.”[17]

There, there is the truth. His madness comes from within, like all psychoses. Freud’s pen flies across the page.

Oedipus and Castration………… Love….

Father-imago……. Feminine attitude. Infancy……….

Complex . . . Narcissism… Psychological Truth! [18]

Ghosts

Freud’s science arrives to explain away everything that is important… Freud gets so close to dealing with the social reality of haunting only to give up the ghost…[19]

In Clara, Freud must have found reason for his horror. If he could quarter it off, draw lines with science, somehow explain his uneasiness, then he could sleep without dreaming of the Sand Man. He would not have to slip away into madness with Nathanael. Yet his analysis is almost too tidy:

The father and Coppelius are the two opposite sides of the father-imago, and later the Professor and Coppola fill this role.

Look: Sigmund Freud lies awake late one night, sweaty, thinking about the Sand-Man. He writes a two and a half page summary of the story, and includes it in an essay on the Uncanny. His main point is that, as Jentsch said, the doll

[1] Hoffmann 185.

[2] Freud 219.

[3] Burke 1.7

[4] Burke 2.1

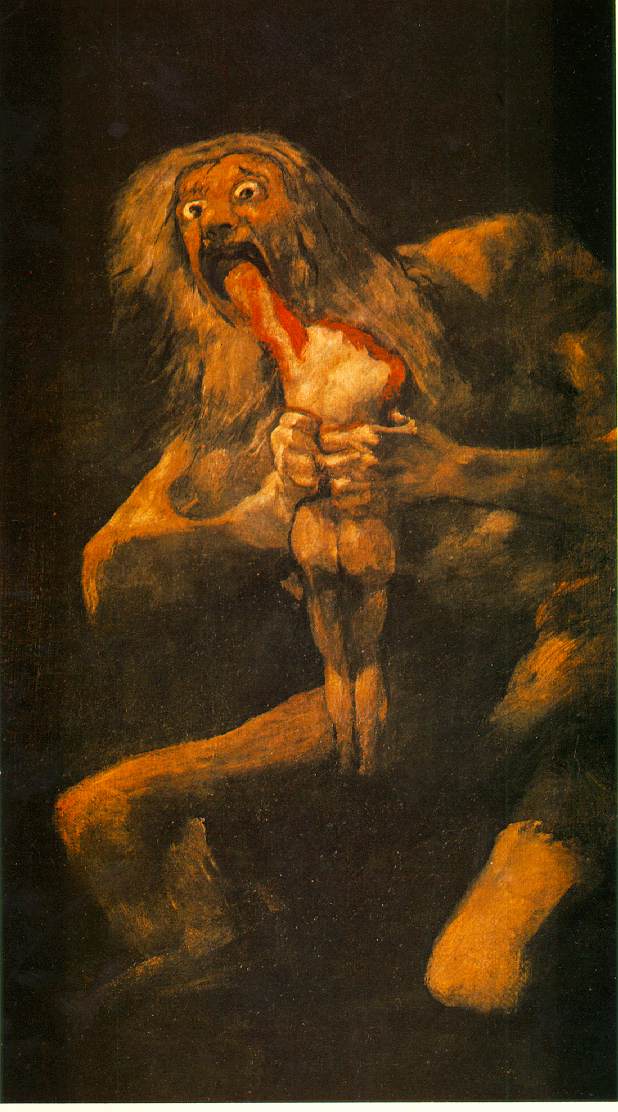

[5] See attached image

[6] Wollstonecraft Shelley 959

[7] Hoffmann 211

[8] Hoffmann 210

[9] Hoffmann 208

[10] Freud 233

[11] Freud 231

[12] Freud 241

[13] Stoker ch. 4

[14] Montaigne

[15] See attached photo

[16] Morrison 261

[17] Hoffmann 191

[18] Freud 232, footnote 1

[19] Gordon 57

[20] Freud 232, footnote 1